Python Memory Management

Python uses a specially tuned memory allocator on top of a general purpose allocator. This suits the universal object model in Python really well, while setting up a nice hierarchy in the memory management system, beginning from the OS’ Virtual Memory Manager to Python’s own object allocator. In this post, I have tried to build up a few concepts while leading up to detailed discussion about the special Python memory allocator. Note: I do not discuss the OS VMM or C malloc.

The Characters

The way I look at it, Python invloves a few characters in this Memory management scheme: The first and the most obvious one being the Memory itself, almost analagous to a book with fixed size pages. Several writers, or the applications and processes on the system, can now use this book to write their own stuff on it. Some of the stuff written long back are not relevant and so, they have to be removed by the garbage collector.

The Python Object Model & CPython

Memory management is nothing but the process by which applications read and write data. Since there’s only a finite amount of storage space available at any given time, the process responsible for allocating these resources has to be optimized. This process of providing memory is generally called allocation.

One thing to keep in mind is that a Python program goes through several layers of abstraction before it actually interacts with the hardware. That’s one of the flip sides for it being a high level language. One of the layers that the program interacts with before reaching the hardware is the Operating System. Memory management for Python code is handled by the Default Python application installed in the Operating system, called CPython. No points for guessing. It’s actually written in C.

So, what does this Default Python implementation written in C, actually do?: It basically achieves two main tasks:

- Interpret written code based on the rules referenced in the reference manual. This is essentially the step where your Python code is interpreted into bytecode. This bytecode is actually saved in the

.pycor__pycache__folder. - Execute this interpreted bytecode on a virtual machine.

CPython has a few limitations as well. Firstly, it is written in C and therefore, has no Object Oriented features. To imitate Python’s universal object model, CPython creates a struct called PyObject, which every other object in CPython uses. struct can be considered to a grouping of different data types. This PyObject contains two things:

ob_refcnt: Reference Count.ob_type: Pointer to another type. The object type is just another struct that describes a Python object.

Each object also gets its own specific memory allocator and memory deallocator that can get and free up the required memory space, respectively.

TLDR: CPython(aka the Default Python Implementation) sits in your OS and achieves the task of executing your Python code. This is also where the Memory management algorithms and structures exist.

Interpreter Lock and Garbage Collection

Since our systems are not blessed with infinite memory, there are often situations when a block of memory can have conflicting claims. We would not want such a mess. The Global Interpreter Lock ensures that only one process can write on the memory at a time. This also achieves the objective of no shared claims to a single resource. The Interpreter Lock is literally a global lock on the interpreter when a process is interacting with a shared resource.

When a block of data is no longer referenced, the garbage collector swoops in and frees the memory space so that other objects can use it. This happens when the ob_refcnt drops to 0 for a specific object. You can check this using the sys.getrefcount(object) method.

Default Implementation Memory Management

As I mentioned before, one of the several layers of abstraction that a Python program has to go through before it interacts with the physical memory is the Operating System. The OS essentially creates a virtual memory as a layer that is accessed by Python and other applications. The OS is responsible for carving out a chunk of memory and assign it to a Python process.

Out of the assigned memroy, Python uses a portion for internal use and non-object memory. The other portion is to store objects. The CPython Object allocator works in the latter area and gets called every time an object needs to be allocated or deleted. The allocator is essentially built in as a fast, special purpose memory allocator on top of a general purpose malloc. It is optimized heavily to work with small amounts of data at a time. We will also look at the general memory allocation strategy in C.

PyMalloc

We should first discuss a bit about the abstractions that the object allocator uses: arena, pool, and block.

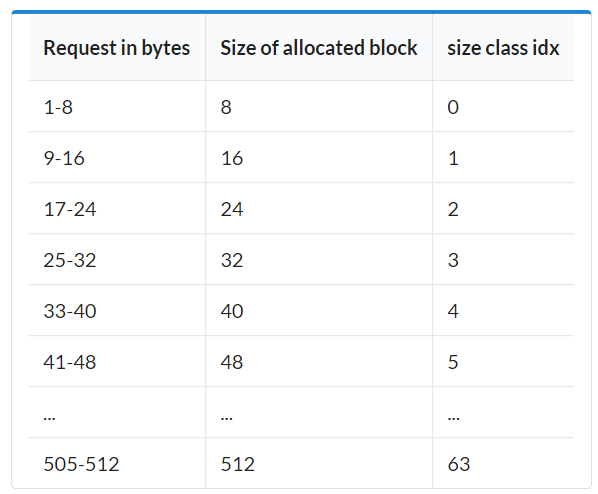

- The Block is the smallest structure. It is basically a chunk of memory of a certain size and it can keep only one Python object of a fixed size. The size can vary as shown in the table.

- A collection of blocks of the same size is called a Pool and the size of a pool is equal to the size of a memory page, ie 4KB. Pools of the same size are linked together using doubly linked lists and has some fields that store critical data:

szidx: keeps the size class index of the blocks that constitute the poolref.count: Number of blocks used to create the poolarenaindex: Stores the number of arena in which the pool was created.freeblock: freeblock points to the start of a singly linked list of free blocks within the pool. All the available blocks in a pool are NOT linked all together when a pool is initialized. This is in accordance with the zen of python: Never to touch a piece of memory unless it’s actually needed. Only the first two blocks are set up. If a block is empty, it stores the address of the next empty block instead of an object. A Pool also has three associated states:- Used: Neither full nor empty

- Full: All blocks allocated

- Empty: All blocks available

- An Arena is a 256KB chunk of memory providing space for 64 pools(64 pools of 4KB each = 256KB). All arenas are linked using doubly linked list. This is analogous to a list of containers which automatically allocates new memory for pools when needed. The struct associated with an arena looks like:

struct arena_object{

uintptr_t address;

block* pool_address;

uint nfreepools;

uint ntotalpools;

struct pool_header* freepools;

struct arena_object* nextarena;

struct arena_object* prevarena;

};

It is interesting to note that PyMalloc rarely returns memory back to the Operating System. An arena is released completely if all its pools are empty. This might lead to a lot of unused memory for long running processes.

TLDR: Python has a dedicated object allocator for small objects(smaller or equal to 512 Bytes). This keeps some chunks of already allocated memory for further use in the future. In most cases, this memory is never released and is abstracted through three levels: arenas, pools and blocks.

Thank you!